Beginning December 10, a series of powerful tornadoes swept across six states in the Midwest and South (Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, Mississippi, and Tennessee), killing close to 100 people and destroying countless homes, businesses, and other property. In a press briefing, Kentucky Governor Andy Beshear called the series of storms “the most devastating tornado event” in state history.

Tornadoes in the U.S. cause an average of $5.4 billion in storm damage each year, according to a report published in the journal Nature Portfolio. Downed electrical lines are a given following a tornado, and loss of other utility services such as water is also common.

Utility infrastructure’s susceptibility to extreme weather varies from location to location, but no critical infrastructure is entirely protected from storm damage. In some areas, infrastructure is facing new extreme weather events. For example, while the frequency of tornadoes has remained constant, their location has shifted, migrating from so-called “tornado alley” in the Southwest and western Midwest to the Southeast and eastern Midwest, according to the Nature Portfolio research report.

It's essential utility companies know the types of extreme weather events their infrastructure faces, so they can implement the best critical infrastructure protection plan. Fortunately, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has performed extensive research surrounding natural hazards, publishing their most recent findings in the National Risk Index in November 2021. Using the All Counties - County-level detail dataset—found on this webpage—we created maps of the contiguous 48 states that show where certain extreme weather events will have the most impact on people and critical infrastructure. We also created one map that shows overall risk for all the extreme weather events we examined.

Is your critical infrastructure highly vulnerable to extreme weather conditions? Read on to find out.

Extreme weather events that threaten critical utility infrastructure

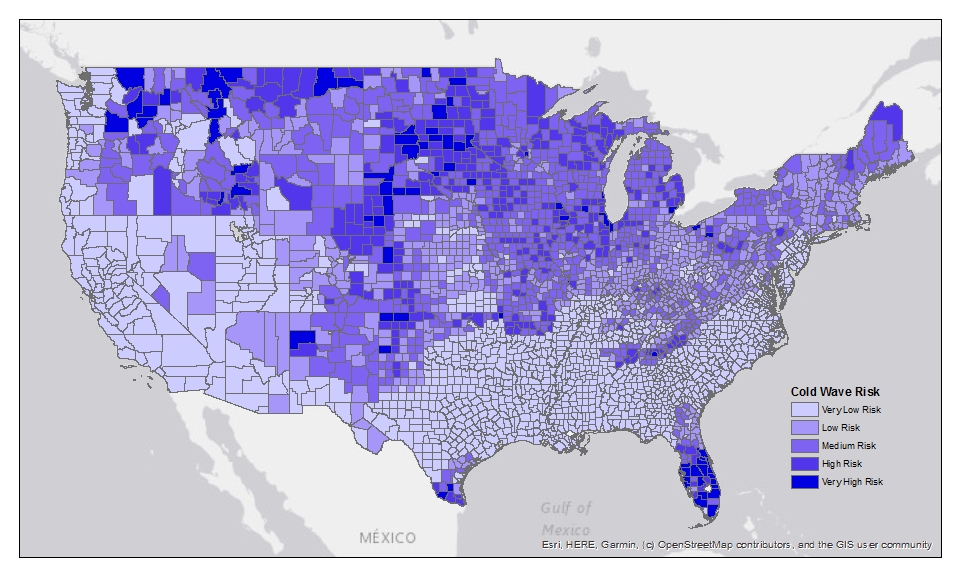

Cold wave risk

A cold wave is an expeditious fall in temperature within 24 hours with extreme low temperatures—possibly accompanied by wind chill and frost/freezing—for an extended period. Cold waves can occur almost anywhere in the U.S., but classification of a cold wave is dependent on the location. So, a cold wave in South Dakota—where the average low temperature in January is below 10 degrees Fahrenheit, according to travelsouthdakota.com—would feel much different from a cold wave in Florida, the overall warmest state in the U.S., according to the website World Population Review.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the areas most at risk for cold waves are primarily located in the northern U.S., although areas in some southern states—notably Florida, Texas, and New Mexico—also show high or very high risk.

Extreme cold weather can put energy supplies at heightened risk, as demonstrated by the cold wave that struck Texas and several other central states in February 2021. Cold waves can also damage utility infrastructure. Research shows gas pipelines are most at risk to leak or break after five consecutive days with a high daily temperature below 32 degrees Fahrenheit. These periods of sustained freezing have occurred in cities across seven states every year for the last five years.

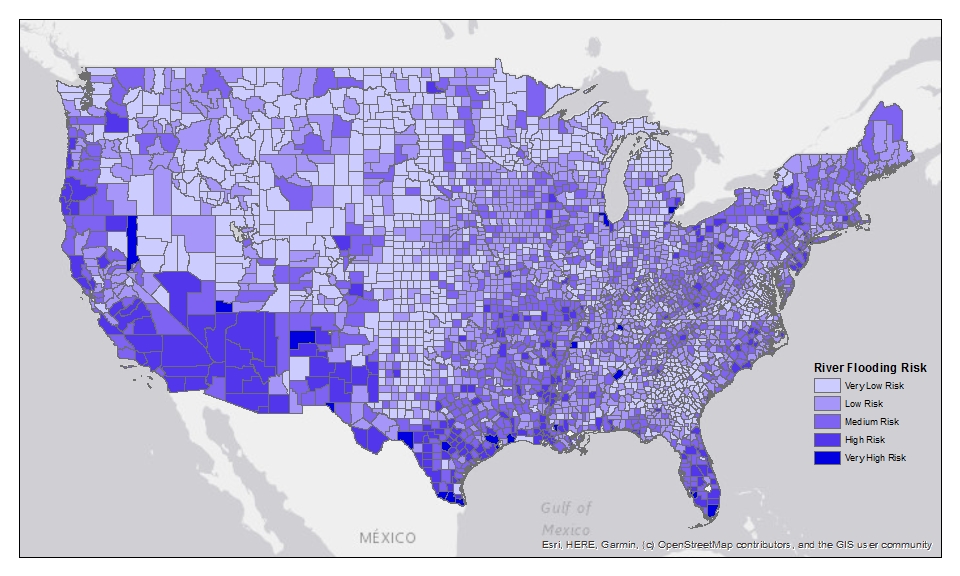

River flooding risk

River flooding is when streams or rivers overflow, spilling water into adjacent low-lying, dry land. Heavy rainfall and thunderstorms are often the culprits for river flooding, and flash floods are a common result.

According to FEMA, nearly every county in the U.S. has sustained some form of loss due to river flooding. The areas most at risk for river flooding, however, are primarily located in the Southwest and West.

Southern California and Arizona are at the highest risk for river flooding. These areas are also at a high risk for wildfires, which strip the land of vegetation and leave the ground unable to absorb water. According to FEMA, flooding after fires is particularly severe, as debris leftover from the fire can form mudflows, which can cause significant damage to critical infrastructure, among other properties.

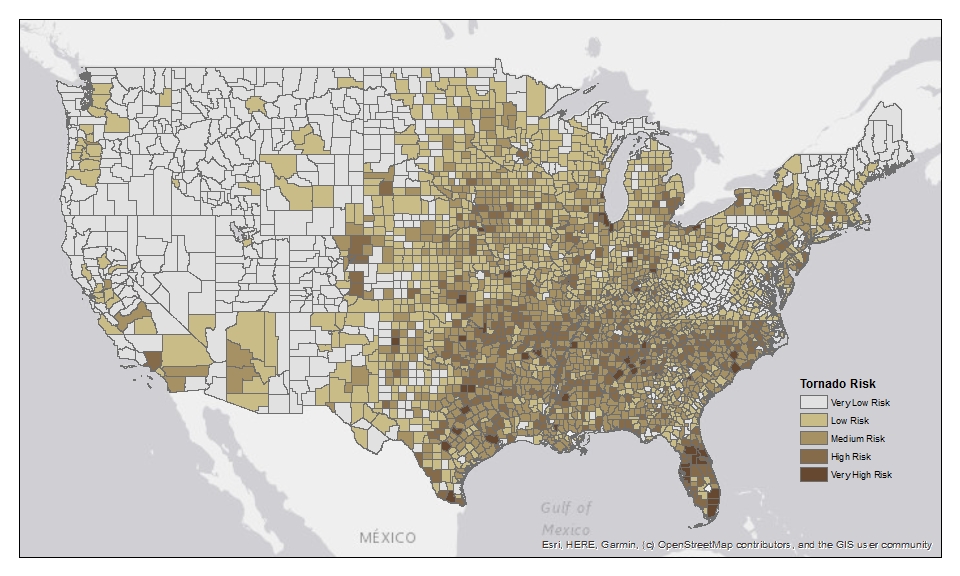

Tornado risk

A tornado is a narrow, rotating column of air made up of water, dust, and debris that stretches from the base of a thunderstorm to the ground. Under the right conditions, tornadoes can occur almost anywhere.

Tornadoes are historically common in the Great Plains, though they’re becoming more common in the Southeast and Midwest, as mentioned previously. The below map shows a smattering of very high and high risk areas in all of these regions. The Mid-Atlantic region also has pockets of areas with high risk for tornadoes.

Like the size of tornadoes themselves, the size of the damage area can vary widely. And while some tornadoes do little damage, the most powerful tornadoes can easily pluck utility poles from the ground and annihilate substations in their path, leaving homes and businesses that remain without essential services for weeks or months.

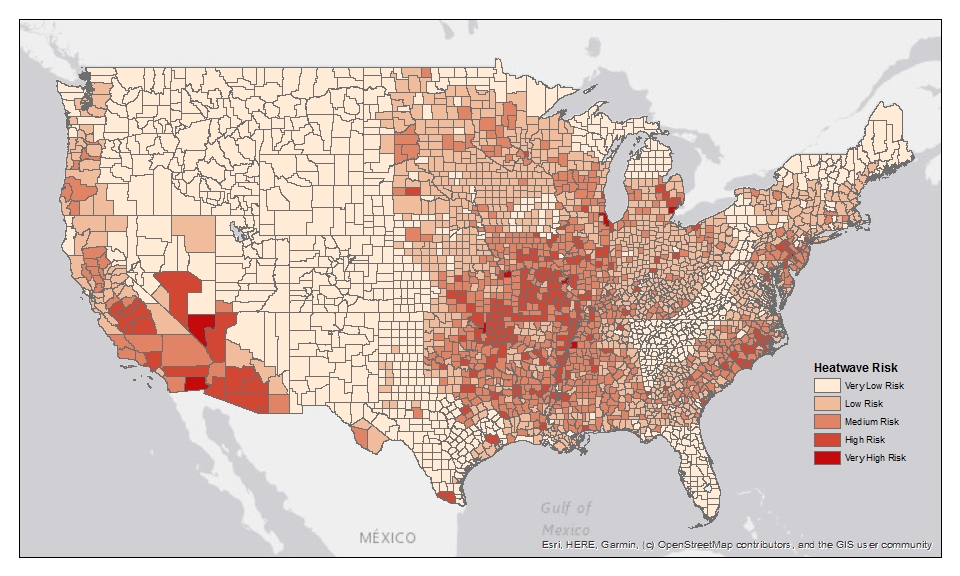

Heatwave risk

A heatwave is a period of exceptionally hot, possibly humid, weather with temperatures outside the historical averages that lasts at least two days. Like cold waves, heatwaves can happen almost anywhere in the U.S., but temperatures classified as a heatwave are dependent on the location.

Certain areas in the West and Southwest are at very high risk for heatwaves. In 2020 in Death Valley, CA, a maximum temperature of 130 degrees Fahrenheit was recorded, according to the 2020 Global Climate Report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA). Large areas in the Midwest and Southeast are at high or medium risk for heatwaves, as are many areas along the East Coast.

In recent years, utility companies in these areas have instituted power shut-offs to avoid a total blackout when consumers’ demand to cool their homes and businesses during a heatwave exceeds the power supply capability of the network. This can, unfortunately, create dangerous situations for vulnerable or health-compromised consumers. Intermittent energy access also causes economic problems for affected businesses.

You might like: 4 Fiber Outages that Show Telecom Damage Prevention is Critical

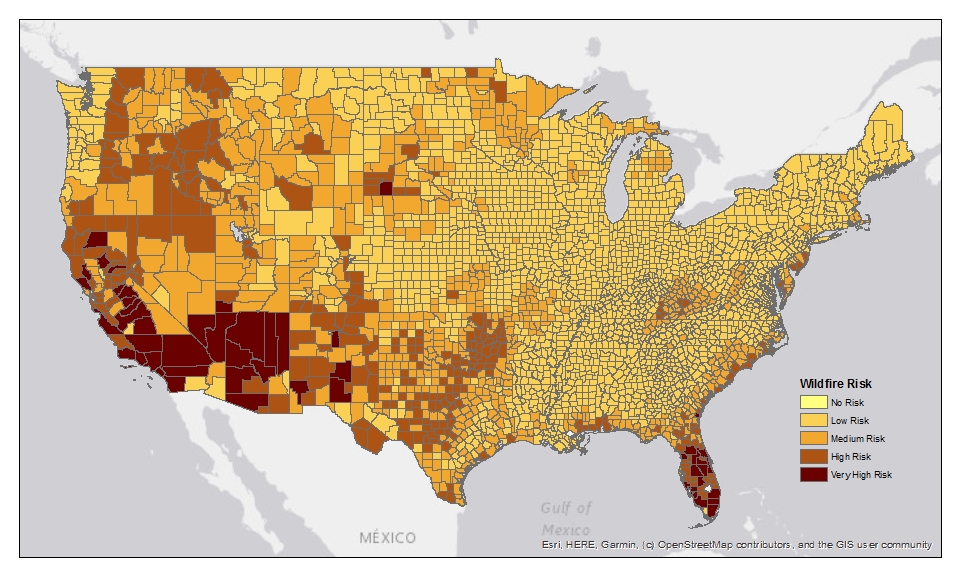

Wildfire risk

A wildfire is an unplanned fire that burns in natural or wildland areas, such as forests, shrublands, grasslands, or prairies. Wildfires have burned in the U.S. for centuries, though the number, intensity, and duration of fires have increased in recent decades, at least in part due to increasing bouts of hot weather.

Large swaths of California, Arizona, and Nevada are the most at risk for wildfires. Other Southwest, Northwest, and Midwest states are also susceptible—and more areas may be at risk in the near future. According to the New York Times, by the 2040s, the number of wildfires could increase by 20 percent, and the total burned area could increase by more than 25 percent.

Wildfires can consume everything in their path, including utility infrastructure, and restoration and repairs can take months. For improved critical infrastructure protection, some utility companies in areas at high risk for wildfires are working on plans to bury more distribution lines.

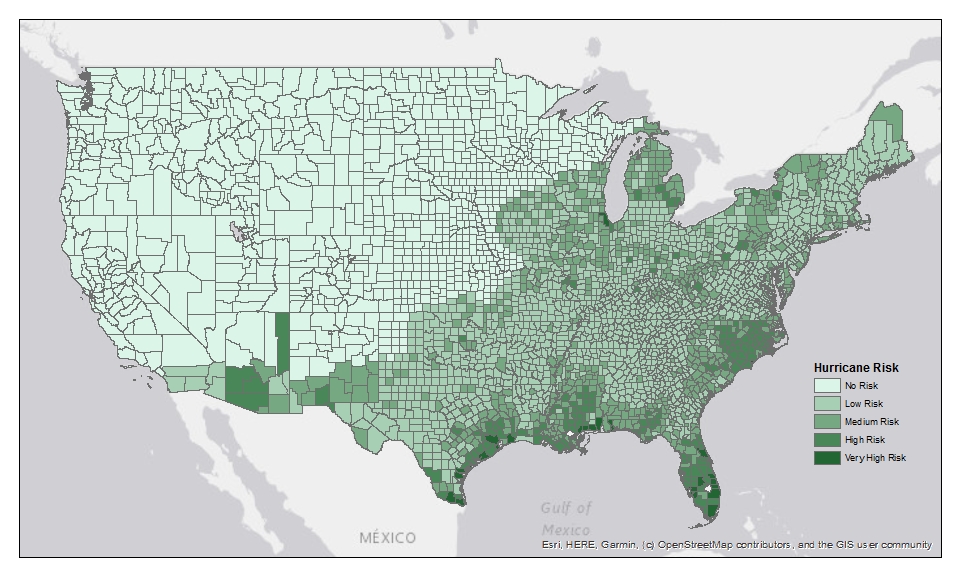

Hurricane risk

A hurricane is a tropical cyclone or a localized, low-pressure weather system that forms over the Atlantic Ocean or eastern Pacific Ocean. A hurricane has organized thunderstorms, but no weather fronts, and maximum sustained winds of at least 74 miles per hour (mph). Areas susceptible to hurricanes can also be affected by tropical storms, which have wind speeds ranging from 39 to 74 mph.

The entire Northwest is free from hurricane risk, though it may be surprising that sections of the West, Southwest, and Midwest are not. While the likelihood of hurricanes in these areas are low, the consequences of a storm could be quite severe in highly populous areas—like Chicago’s Cook County, the second-most populous county in the U.S. Coastal areas along the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico have the highest risk of hurricanes. According to NOAA, there were 30 tropical storms and 13 hurricanes in the Atlantic Ocean in 2020, the highest ever in a single year.

Like wildfires, hurricanes are not a new threat to critical infrastructure, but they have grown in number and severity. Storm damage prevention investments to harden critical utility infrastructure have paid off, as made evident following Hurricane Irma in 2017 when Florida utilities were able to restore service mere days after the storm.

Check out: Why Only Some Hurricanes Cause Massive Power Outages

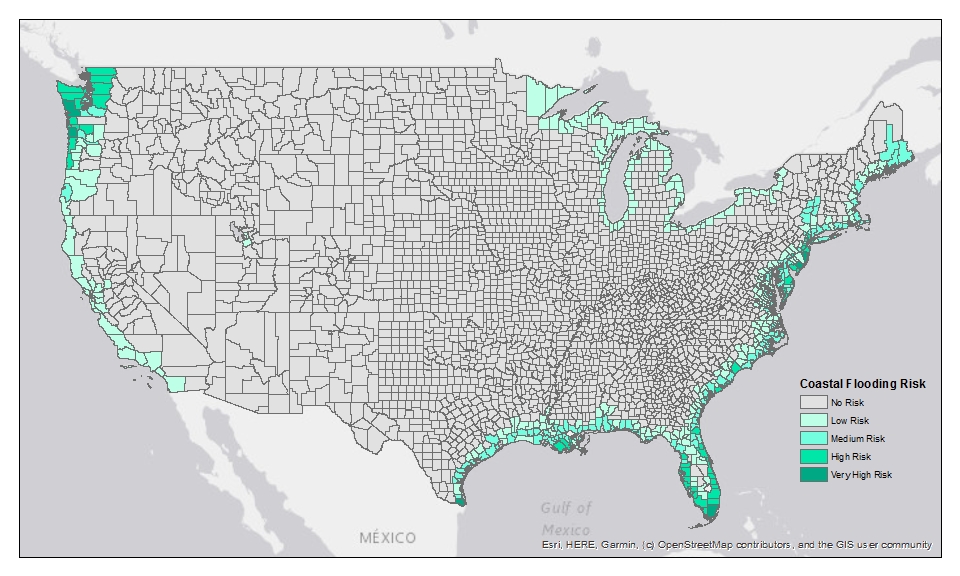

Coastal flooding risk

Coastal flooding is when water covers coastal land that is normally dry due to high or rising tides or storms such as hurricanes. Areas along the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans and the Gulf of Mexico are susceptible to coastal flooding, as are areas along the Great Lakes and even a few counties along the Great Salt Lake in Utah.

Critical infrastructure in the Northwest, particularly Seattle and its surrounding areas, as well as infrastructure along the east and west coasts of Florida are at very high risk from coastal flooding. This is primarily due to the high number of people who would be affected should the infrastructure be compromised. Although not included in our analysis, Alaskan infrastructure is also at very high risk from coastal flooding.

Also see: 20 Regions Where Utility Damages Could Rise in 2021

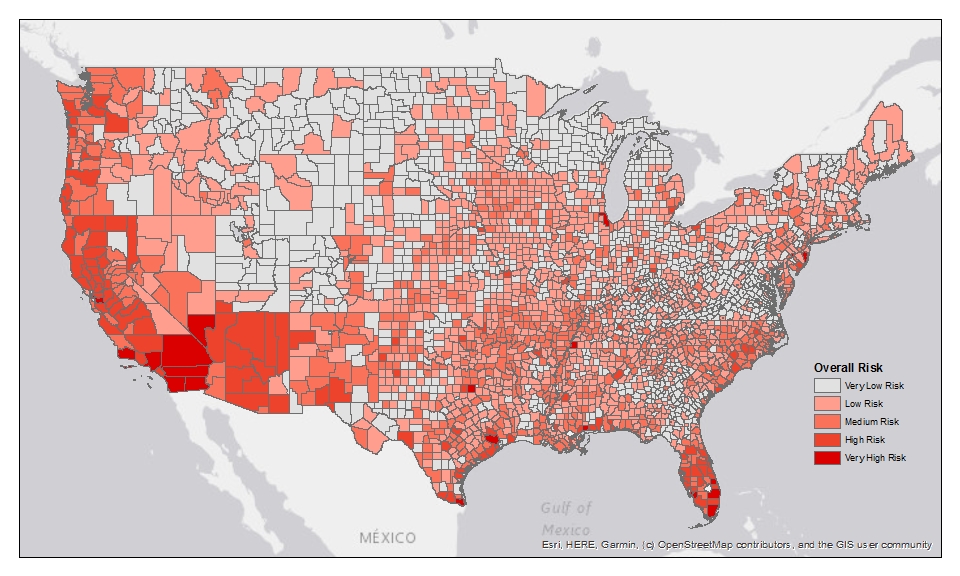

Overall risk

A 2020 Yale survey revealed that less than half of Americans (43 percent) think climate change and the effects it has on weather will harm them personally. Yet, FEMA research shows every geographical area in the U.S.—and its critical infrastructure—is at risk from at least one type of extreme weather. That said, some areas are at greater overall risk from extreme weather events because they are highly populated, they face multiple threats, and the potential damage to property is high.

The below map shows the areas with the greatest risk considering all of the previously mentioned extreme weather events (cold wave, river flooding, heatwave, wildfire, hurricane, and coastal flooding). In the contiguous U.S., critical infrastructure in the West (California and Nevada), South West (Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas), North West (Washington and Oregon), and South East (notably, Florida) are the most at risk for damage or destruction due to extreme weather.

Recent extreme weather events, like the tornadoes in the Midwest and South, demonstrate that critical utility infrastructure can be rendered inoperable in a matter of minutes. It is the responsibility of utility companies to do everything they can to harden their infrastructure to withstand extreme weather conditions so they can provide essential services to consumers in their greatest time of need.

For similar content, check out “Why the Pandemic Makes Infrastructure Damage Prevention More Important Than Ever.”

Methodology: Urbint created the above maps in ArcGIS using the “Hazard Type Risk Index Score” data points of the FEMA National Risk Index All Counties - County-level detail (Geodatabase) dataset, found on this webpage. The National Risk Index Technical Documentation helps illustrate the U.S. communities most at risk for 18 natural hazards based on the likelihood and consequence of the natural hazards. Page 2-1 of the shows the timeline for development of the National Risk Index, which indicates work began in 2016 and Phase 1 of the National Risk Index was released in Fall 2020. Urbint examined seven of these natural hazards (cold wave, river flooding, tornado, heatwave, wildfire, hurricane, and coastal flooding), which the team determined were the most relevant for utility companies as it pertains to their critical infrastructure.